25 June 2019

3 Lessons On Why The Toronto Raptors Won Their First NBA Title

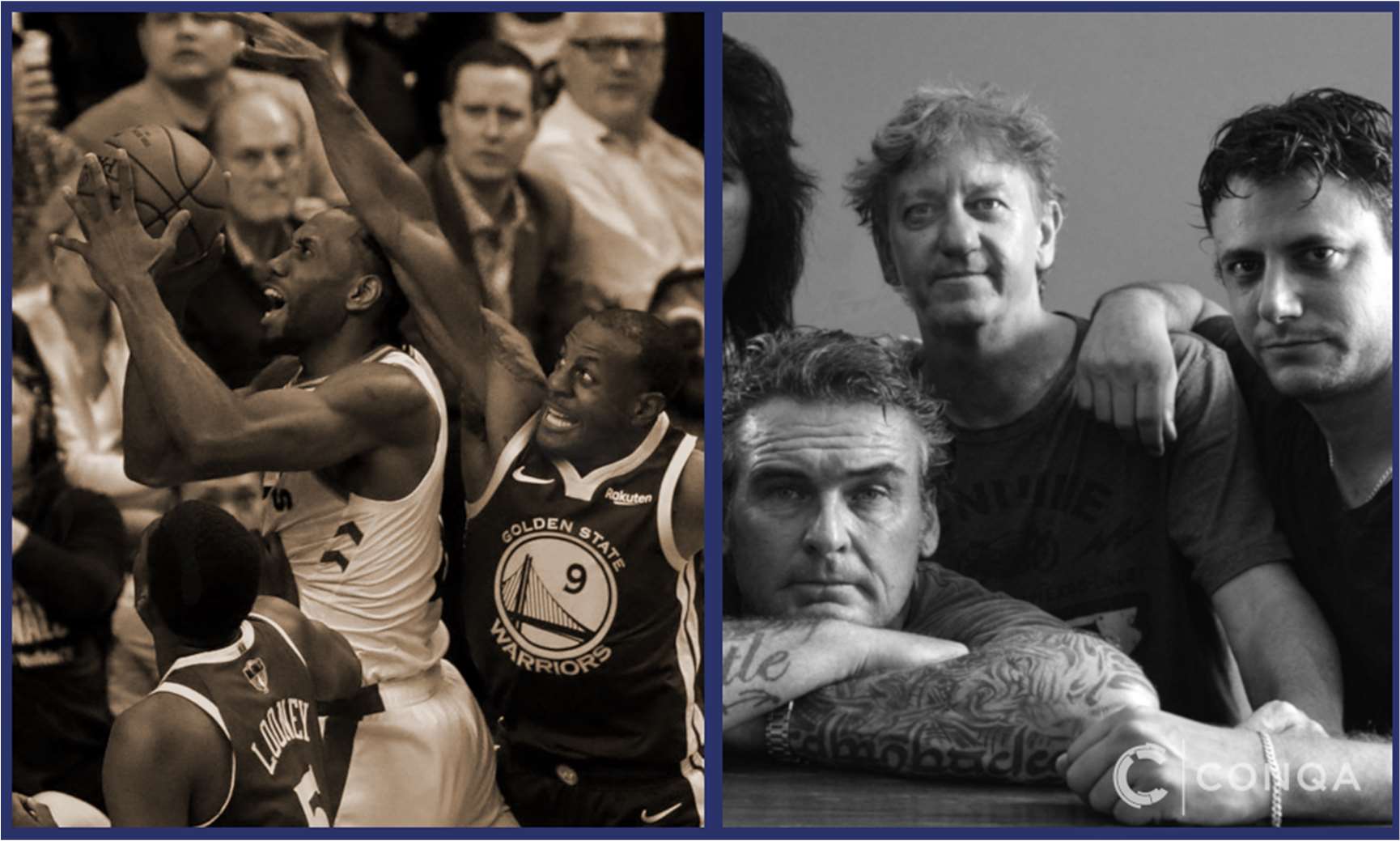

With the basketball thudding as your opponent stares at your move from every angle, that split-second moment makes all the difference: one wrong move and all might be lost to the other side.

But for the Toronto Raptors, that brief moment of silence was broken by roaring cheer throughout the stadium – Claw had just made the winning shot and won his team their first NBA title.

To many NBA-enthusiasts, those split-second moments are a roll of the dice: the Canadian team’s win may come as a surprise, but a mix of luck and moves made by accident are surely what got them there.

But as song artist and team ambassador Drake knows from his own career, that is not quite the case: the artist’s latest victory parade might seem more to do with signing merchandise, with the team’s win, a gift of luck to celebrate – but he and the team know that there is more behind the scenes.

Every instinct, every move – and ultimately every winning shot – has years of rigorous training and fine-tuned leadership to back it up. There are three lessons every sports leader can learn from this big win, and one of these ingredients might have been fuelling this upward rise all along.

#1 SUCCESS IS THE TIP OF THE ICEBERG. FOCUS ON THE TRAINING BEHIND IT

We all recognise that success is earned – not stumbled upon by chance. But when absorbed by the thrill of watching our favourite teams compete in real-time, this is easy to forget.

In fact, a more realistic understanding of what enables athletes to succeed might not even seem relevant to the enthusiastic viewer: sport is a primal entertainment format, and the idea of ‘winning by chance’ is so much more attractive when enjoying the thrill of the ride.

But this distorts the actual sources of success. In reality, even the most ‘real-time’ and intuitive decisions made on the sports field are fine-tuned in advance through rigorous training: as a sports leader, this means accepting that the success of your team means hundreds of hours of practice – not just the motivating locker-room speech on the big day.

In fact, according to James Clear, author of the book ‘Atomic Habits’, this aggregation of training increments is much more than a fleeting concept: James argues that – although leadership does play a critical role in priming a sports team emotionally for the big game – an estimated 70% of real-time sports decisions are actually ‘pre-programmed’ in advance through extensive repetition. Moreover, unlike the intuitive training schedules followed by more amateur teams prior to an upcoming game, professional teams are also found to plan this ‘repetition training’ over a much longer period (Seiler, 2010): this effectively ‘pre-programs’ the players with a much larger number of trained responses in advance – winning moves become automatic, even without the mental bandwidth.

#2 YOUR TEAM NEEDS A WINNING CULTURE – NOT AN EXERCISE MANUAL

Truly ‘automating’ your team’s winning in-game tactics may mean restructured and longer training sessions.

But unlocking the winning culture among your team that is needed to fight pressure on the big day requires a restructuring of something else – and that’s your leadership behaviour.

With the correct practice and training in-place, your team will be looking for you to lead a winning culture – not an exercise manual.

Unlike the lecturer preparing his class for the next maths assignment, the mechanics of any winning sports move has emotion baked right into it: this means that cognitively preparing your team members with the correct motor responses is not enough – your team is entering ‘combat mode’, and that means providing a blueprint of emotions that can kick in when logic is left behind.

The ‘stress-response curve’ for athletic performance. Ashwani Bali, 2015.

This ‘combat mode’ effect is well known for sport activities, but also impacts other team activities with a strong ‘real-time’ component: expanding on the three-stage stress management model (Bali, 2015), one study at the University of Groningen indicates that existing methodologies used by musical groups to mitigate stage fright may also help manage the pressures of a real-time scenario (Mak, 2010): just as with the rhythmic moves of bouncing a ball in-game, the rhythmic sequences needed for our brain to play an instrument in real-time require an emotional reference-point to fall back on.

This highlights that rather than being a compliment to prior practice and training – the cultural motives that a group leader imprints onto his team members can act as a tool to reduce the effects of real-time pressure when mental bandwidth is no longer available.

#3 HUMILITY MIGHT MEAN A LATER SUCCESS – BUT THEN A ROARING WIN

As with any field with a strong ‘leadership’ component, any methodology can only be as effective as the learner is open to learning it to begin with. This may seem obvious on the surface, but when we think of any creative or real-time activity, we see where the barriers can crop up.

Drake would tell us first-hand that even innate talent has its glass ceiling: bridging this talent into the pressure of a real-time audience requires rigorous tuning of one’s own behaviour; having the humility to emulate those already ahead; and training a band to handle similar pressures would just not work without having undergone the behavioural tuning – and from the top.

And if we listen to the science, the causes of a ‘glass ceiling’ among sports coaches could be the same: one study from Springer Science demonstrates that the tendency to engage in personal development; extracurricular learning in the seminar format; and ‘stance-revaluation’ does correlate to higher performance among professional athletes.

Although extracurricular development may appear unrelated to the task of coaching a sports team, this mode of behaviour does create new neural pathways that make it easier to implement the above strategies (Aires, 2014): this means that the strategies of ‘building a winning culture’ or the intuition needed to structure the training for your team require a sort of ‘learning mode’ at the foundation.

Ultimately, switching to this humble ‘mode of learning’ may encourage you to restructure the training of your team over a longer-term. But tuning and adapting your leadership behaviour may be the final ingredient that your team culture needs to push for the roaring win.

KEY OUTCOMES FROM THIS WEEK’S ARTICLE:

In this article, we learned key strategies sports teams are using to maximise performance. These modifications have implications for your own team, and we suggest the following:

On the one hand, to increase the intensity of your training sessions on the run-up to the big day. However, as James Clear suggests, the most ‘hard-wired’ motor responses that will enable your team to perform on the day will necessitate extended periods of practice and repetition. Although practising different sequences and techniques may not seem intuitive months before the big day, think of your team’s performance as an ‘aggregation’ of these training activities – the momentum of your practice will be rewarded.

In addition to tuning the athletic aptitude of your team members, remember that this will reach a glass ceiling shortly before the big day: stress will creep in, and recalling past content will be difficult: naturally, your team members will turn to the more primal alternative of the ‘emotional blueprint’ from your leadership when mental bandwidth is brought to a halt: this means instilling the right culture well in advance and rooting out anti-social behaviours – and this will enable your players to run on this ‘motivation fuel’ as a distraction from the pressure of the game in real-time.